Why Spinal Flexion Exercises Aren't Bad

I don't program standard crunches, but not because I think they're bad. I just prefer spinal flexion exercises that allow you to train through a larger range of motion, such as crunches on a stability ball where you stretch over the ball at the bottom of each rep. (After all, I'm not going to do biceps crunches instead of full-range biceps curls.)

Plus, these types of exercises are more time efficient. They provide a sufficient training stimulus without the endless reps, which is also why I don't use crunches. I also use spinal flexion exercises in conjunction with anti-spinal movement exercises.

Many trainers are against any sort of spinal flexion exercises and exclusively use anti-spinal movement exercises. They take this approach because they argue that spinal flexion exercises are inherently dangerous, bad for your posture, non-functional, etc.

I've debunked these common false beliefs on T Nation before but here are a few more scientific points.

Research has shown the basic crunch elicited around 2,000N of compression on the spine at L4/L5 (1). It's because of that level of spinal compression that many trainers say those exercises should be avoided. However, many of these same trainers will proudly recommend exercises like kettlebell swings and bent-over rows.

Interestingly, spinal loading at the beginning of the swings when using a 16kg kettlebell created 3195N of compression, 2328N at the middle of the swing, and 1903N of compression at the top of the swing (2).

And the bent-over row was shown to create 3,576N on the spine, which is also significantly higher than the compression created on the lumbar spine during a basic crunch (3). So, as Bret Contreras said, "Many coaches vilify certain exercises based on the levels of spinal loading they produce only to prescribe alternative exercises that exceed the levels reached in the exercises they discourage."

Now, some will argue by saying that crunches involve spinal flexion, which is the problem, but the kettlebell swing and the bent-over row don't involve any lumbar flexion. They say to just keep your spine in a safer position to deal with these levels of compression. Unfortunately, this common belief has also been falsified in multiple studies.

There's a multitude of research showing that lumbar flexion occurs when performing a variety of common lifts, even when lifters are cued to maintain a neutral spine while under the watchful eye of experts such as Dr. Stuart McGill:

- Kettlebell Swings: 26 degrees (2)

- Good Mornings: (which involve a very similar positioning at the bottom to a bent-over row) – 25-27 degrees (4,5)

- Squats: 40 degrees (6)

Two studies on squats using men and women found that in every case, as soon as a loaded bar was placed across the rear shoulder region prior to the commencement of the downward phase of the squat, the lumbar spine lost its normal or natural curve (7,8).

Another soon to be published thesis paper titled, "Lumbar spine kinematics and kinetics during heavy barbell squat and deadlift variations," out of the University of Saskatchewan, showed 50% and 80% max flexion on squats and deadlifts respectively.

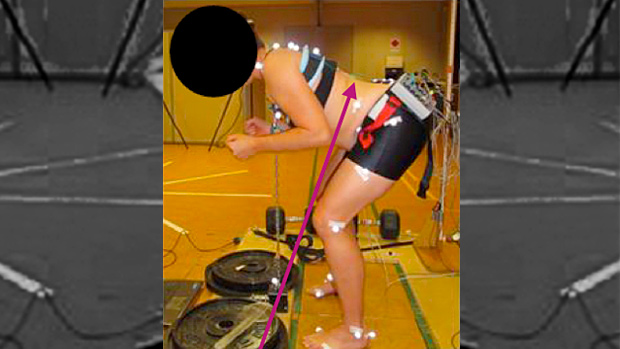

It's impossible for the lumbar to stay in spinal neutral (which is more of a range than a specific spinal position). That's nothing new, as it was demonstrated by biomechanists in 1994 (9). Note how it looks neutral but it's still flexed.

It looks neutral despite it being 22 degrees of lumbar flexion, which is around 35% of max flexion (10). Researchers suggest that what appears to be a neutral-looking lumbar spine position (when it's actually flexing) is in reality the thoracic spine being more neutral (11).

Another reason could be due to normal human variations in pelvic shape, which makes it difficult to accurately determine pelvic posture. Research shows there's considerable morphological variation between pelvises. It's possible that differences of up to 23 degrees in the ASIS-PSIS angle (and 22 degrees in the pubic symphysis-ischial spine angle) could reflect differences in morphology rather than differences in muscular and ligamentous forces acting between the pelvis and adjacent segments (12).

This isn't at all saying there's no need to coach or attempt to maintain a stiff, lordodic lumbar position when you perform these types of exercises. You certainly want to attempt to control your spine and maintain the strongest position you can because you can change the amount of lumbar flexion a little.

It's simply highlighting the fact that some level of lumbar flexion is unavoidable, even when you're trying to actively prevent it. And some level of lumbar spine flexion is going to occur no matter what. You can't accurately call lumbar flexion a reliable risk factor to avoid when it's a normal and unavoidable aspect of many functional movements and common lifts.

- Contreras, B. and Schoenfeld, B. (2011). To crunch or not to crunch: An evidence-based examination of spinal flexion exercises, their potential risks, and their applicability to program design. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 33, 4, 8–18.

- McGill SM, Marshall LW. Kettlebell swing, snatch, and bottoms-up carry: back and hip muscle activation, motion, and low back loads. J Strength Cond Res. 2012 Jan;26(1):16-27.

- Bret Contreras. The Contreras Files: Volume II. Published online 01/17/12.

- Vigotsky, A. D., Harper, E. N., Ryan, D. R., & Contreras, B. (2015). Effects of load on good morning kinematics and EMG activity. PeerJ, 3, e708. doi:10.7717/peerj.708

- Schellenberg et al. (2013) Schellenberg F, Lindorfer J, List R, Taylor WR, Lorenzetti S. Kinetic and kinematic differences between deadlifts and goodmornings. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2013;5:27. doi: 10.1186/2052-1847-5-27.

- Potvin JR, McGill SM, Norman RW. Trunk muscle and lumbar ligament contributions to dynamic lifts with varying degrees of trunk flexion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991 Sep;16(9):1099-107.

- McKean MR, Dunn PK, Burkett BJ. The lumbar and sacrum movement pattern during the back squat exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2010 Oct;24(10):2731-41. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e2e166.

- McKean, Mark & Burkett, Brendan. (2012). Does segment length influence the hip, knee and ankle coordination during the squat movement?. Journal Fitness Research. 1. 23-30.

- Dolan P, Earley M, Adams MA. Bending and compressive stresses acting on the lumbar spine during lifting activities. J Biomech. 1994 Oct;27(10):1237-48.

- Greg Lehman. Reconciling Spinal Flexion and Pain: We Are All Doomed to Failure but Perhaps it Doesn't Matter. Published online April 2, 2018.

- Dolan P, Mannion AF, Adams MA. Passive tissues help the back muscles to generate extensor moments during lifting. J Biomech. 1994 Aug;27(8):1077-85.

- Preece, S. J., Willan, P., Nester, C. J., Graham-Smith, P., Herrington, L., & Bowker, P. (2008). Variation in pelvic morphology may prevent the identification of anterior pelvic tilt. The Journal of manual & manipulative therapy, 16(2), 113-7.